Episode 2:

CC Open GLAM Platform: a conversation with Brigitte Vézina and Camille Françoise

Brigitte Vézina is Director of Policy, Open Culture, and GLAM at Creative Commons. She gets a kick out of tackling the fuzzy legal and policy issues that stand in the way of access, use, re-use and remix of culture, information and knowledge. Before joining CC, she worked as a legal officer at WIPO and then ran her own consultancy, advising Europeana, SPARC Europe and others on copyright matters. Brigitte is a fellow at the Canadian think tank Centre for International Governance Innovation. She holds a bachelor’s degree in law from the Université de Montréal and a master’s in law from Georgetown University. She has been a member of the Bar of Quebec since 2003.

GLAM manager Camille Francoise holds two master's degrees, one in museum studies and the other in digital technologies for cultural institutions. She has co-led several editions of co-creative, community-driven events in the museum field in France. After several professional experiences in museum and library institutions & organisations in France, Belgium, Canada and The Netherlands, notably in digital services and collections departments, she joined the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) as a policy and research officer on copyright and open access. In 2021, she joined Creative Commons as Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums (GLAM) Manager.

Kristina Petrasova has a background in Cultural Heritage Studies and production of cultural cross media projects. From 2019 she works at the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision as project lead digital heritage and public media, focusing on education and re-use of digital audiovisual heritage in creative industries. She is part of the inDICEs project in the area of European intellectual property framework.

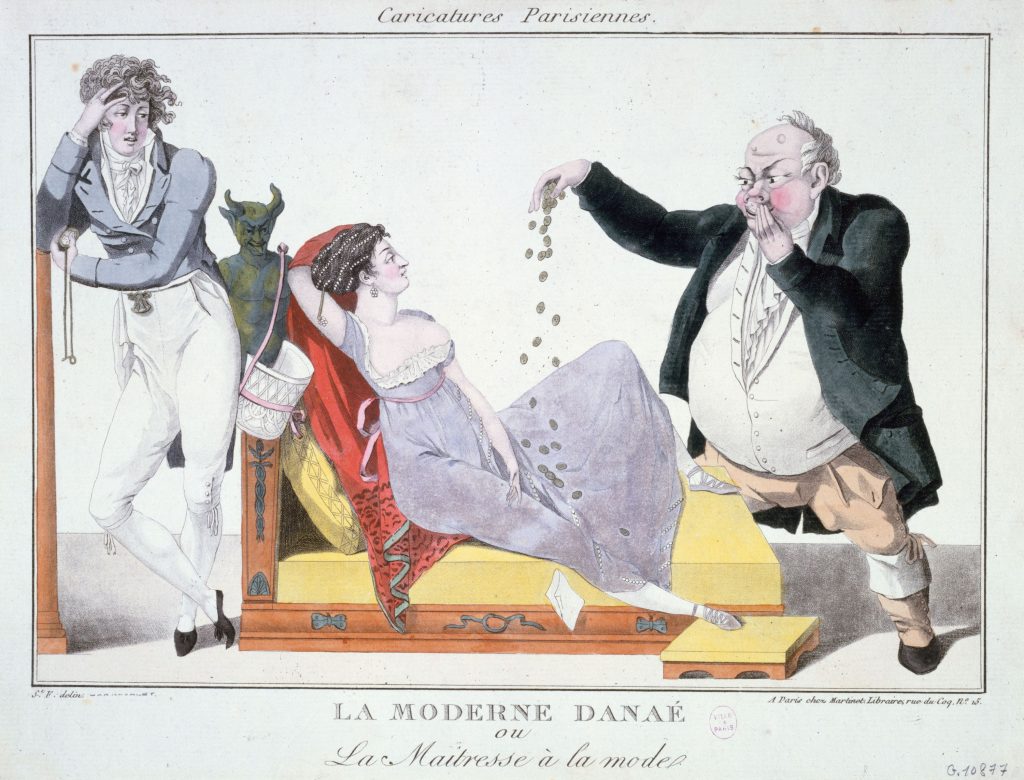

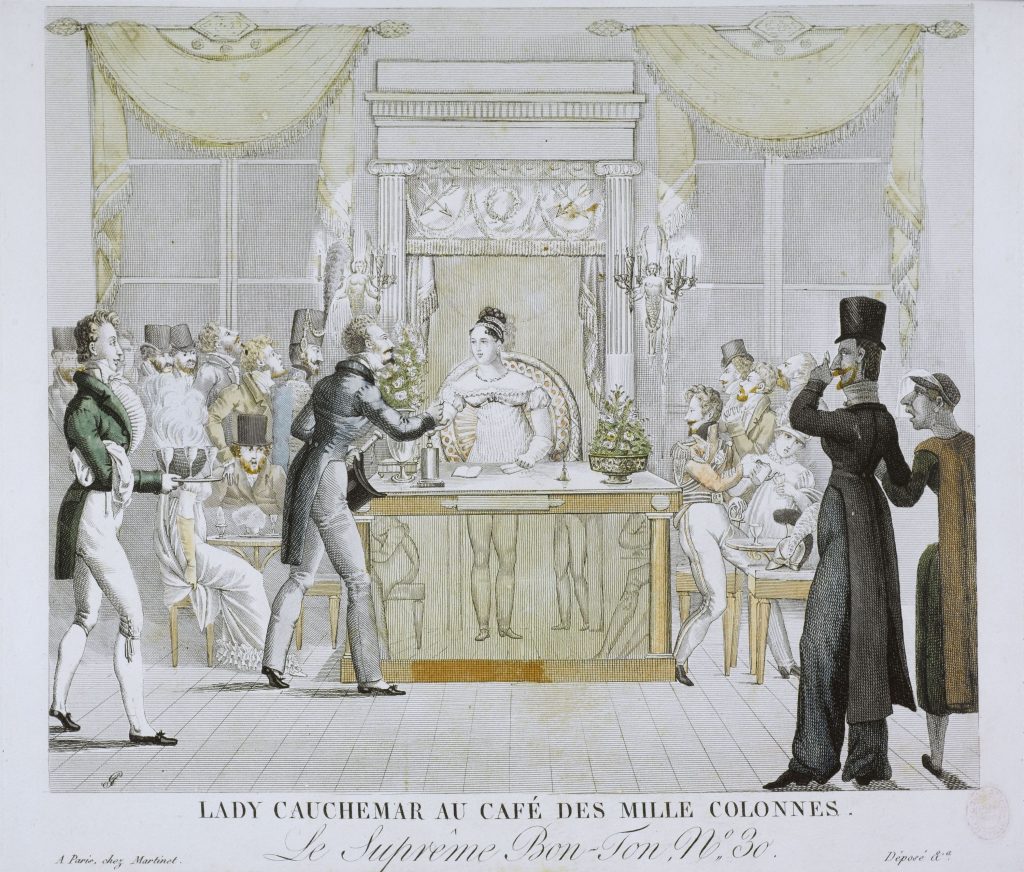

*Images used in this article are from Paris Musées Public Domain Collections

KP: I would like to talk about the work that Creative Commons is doing to encourage cultural institutions to open up, and to connect to the open community. In particular, I would like to zoom in on the current and the future value and the sustainability of Open Access models for cultural institutions. As we find ourselves in the reality of increasing digitality and also crisis on different levels of everyday life, how can we ensure the trustworthiness of digitization in the cultural sector and how can we empower the cultural sector? Let us start with the story behind Open GLAM Platform, how do you envision the platform’s position in the cultural sector?

BV: I can start with a little introduction to where the platform fits within the OpenGLAM program at Creative Commons because it is one of the mechanisms that we have to support and reach out to the community, it’s one of the mechanisms that supports our program. The GLAM program at Creative Commons was launched in June 2021 with generous support from the Arcadia Fund. Its overarching goal is to encourage institutions – galleries, museums, libraries and archives – to make their collections openly accessible, shareable, and reusable. We divided the program into four main components.

The first one is to reshape the policy framework to make sure that the laws in place, that the policies in place support the activities and help GLAMs fulfil their mission. We want to make sure, for example, that copyright is not a hurdle that prevents GLAMs from sharing, but on the contrary that it’s enabling them to do so. So, the first component is mostly about copyright, mostly about ensuring that the exceptions and limitations in the law are there to support institutions, and enable them to give access to their collections, to their users. The second component is about the infrastructure and that is the one that’s closest to Creative Commons’ value proposition, which is CC licences and tools that create the infrastructure for exchanges and sharing of cultural heritage to happen online. We just launched a survey on Public Domain Day, to see if the current tools that Creative Commons has to release or to identify works in the Public Domain are fit for purpose for the GLAM sector. We expect to hear that some aspects of the tools will work, some aspects will need improvement, and we really look forward to seeing what Creative Commons could do to make sure that this infrastructure really meets the needs of the GLAM sector. The third component of the program is capacity building where we provide knowledge and skills, and encourage GLAM professionals working in institutions to understand what are the copyright issues, to understand how to deal with them and how the licences and tools are actually mechanisms to work with the current copyright system that we have in order to provide access and enable sharing of collections. And then the fourth component is community engagement and this is where the platform is. It’s our main space that we make available to anyone. You don’t have to be a network member, you don’t have to be part of the CC Network to participate. It’s open to anyone who has an interest in open GLAM to share their experiences, their ideas, their challenges and have conversations on what the emerging issues are, and what we can all do together to overcome these issues.

CF: The platform is open to everyone. Professionals from cultural heritage organisations, but we are also open to the bigger cultural ecosystem. Performative arts, students or people that are interested in open access and are contributing to culture in any way. We are currently launching working groups where we will focus on six different topics that we will soon communicate. Some issues that we are actually currently seeing in the field of open GLAM have changed and evolved over a couple of years. We also had a new copyright reform in Europe and we also see new challenges emerging. It’s a constant evolution in the field. One of the goals of those working groups is to be able to tackle those challenges as a community in supporting and finding solutions. We will continue to develop over time. The working group topics are currently under discussion and people interested to join any of the groups can do so through our web page.

KP: You mentioned the challenges and issues that cultural organisations encounter. Why should organisations consider opening up, looking in detail at both the core benefits but also the potential risks of open approach? What are the challenges and issues for institutions?

BV: Currently we are reaching out to the community and experts to learn and get involved in the conversations about those advantages and challenges. Also, we are releasing the Open Culture Voices series that is gathering statements from dozens of experts from around the world who are sharing their perspectives from their experience. What are the advantages? What are the benefits? What are the challenges? Where are the barriers? They also give very specific advice to assuage those fears that some have that could prevent institutions from opening up. Some of the benefits relate to how institutions operate internally. Open access is actually an improvement internally that can improve workflows in their organisation, for example how staff is allocated to different tasks. We also see better use of resources and it enables a more sustainable financial model. The fact that many institutions don’t think that it’s financially sustainable to release content for free is a challenge, but we’re also investigating where we want to do some more research on business models. That could support institutions in opening up. It’s fundamentally more mission-aligned.

I think that the core message is that GLAMs are meant to be sharing their collection and in the digital era that sharing happens online. And the best way to accomplish that mission is to make sure that there are no barriers for the public to access and reuse those collections in terms of external benefits. It makes institutions more relevant in today’s digital society. We’ve heard from many experts that if your collection is not online, it just doesn’t exist. Now, people are so used to searching the internet to find that information that if they don’t see it on a website, they probably don’t know that it exists somewhere in a physical space. So to me, that’s a clear signal that GLAMs need to pivot from simply an in-person, physical offering to something that is wider and that can reach more global audiences worldwide. We really want to make sure that Creative Commons is there to support, emphasise and empower the cultural community. We want to raise the voices of experts from outside to make sure that those messages resonate in the open GLAM space.

CF: Many cultural institutions are public services, have a mission to care for what has been created by others and to be able to share it from a cultural perspective. I think for cultural institutions it’s a duty to share the collection they hold. There are so many collections that are actually taken care of, are acquired, conserved – they are aimed to be shared. We are looking forward to having more results on the research, especially on sustainable business models. we see that there is a switch toward a value model that actually can emerge from openness.

KP: From the Creative Commons perspective, what is the link between opening up collections, sustainable information and preservation, and the public value of cultural heritage?

BV: I think that opening up and enabling access to culture and knowledge is fundamental for any society to be sustainable and.nd to thrive when people don’t have access to information, knowledge, culture, and education that can convey these elements, societies cannot function, cannot evolve, cannot thrive. So to me, it’s a necessary component to free and democratic societies and it’s towards that goal that we want to promote and encourage institutions to participate in the dissemination of culture in society in fulfilment of the United Nations sustainable development goals. We also think that it supports fundamental rights, the right to access to culture, according to the UN Declaration of Human Rights. This also concerns education and many of the principles that are enshrined in UNESCO conventions, on the protection of the world heritage, on the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage, on the protection and promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions, etc.

Caricatures parisiennes, le goût du jour numéro 2 – amusement au hameau de Chantilly, Anonymous

All these objectives are served by enabling greater, better access to cultural heritage, especially those that are held in the collections of cultural institutions. I think that there are social and cultural benefits to sharing them., because when members of society have access to culture, it increases their well-being and increases dialogues between communities, it empowers communities to shape the future, according to the information that they have access to and to make their decisions on how they want to participate in civic life and build their future. Preserving and conserving the memory, the legacy of our past generations is essential for current and also future generations for its continuation, this passage of what it means to be human. That is so fundamental to make sure that our societies are sustainable and resilient now and in the future.

KP: How can the envisioned CC Open GLAM Platform contribute to opening up cultural heritage and support cultural institutions in holding up that sustainability?

CF: We are interested to have more academic evidence, more cases and background on the business model to develop correct visibility on sustainable, and open business models in GLAMs. There is a growing interest and need in the sector as we can see by the interest in our meetings and events. A very important topic that is raising is around folklore and indigenous collections now in the field not only from indigenous communities but also because of issues around colonial past, and institutions need to define their positions. Currently, there is a lot of discussion around those topics. The Open GLAM Platform can be a safe and supportive space where we can have those discussions and to integrate the question of ethical sharing.

BV: The motto at the moment of Creative Commons is ‘Better sharing for a brighter future’, as hinted at in our new strategy. Step-by-step we are going towards this discussion and also to help the community take a sustainable position as well as institutions that are related to those communities as well. So that’s one point. And now I think that’s a great overview. I think the main advantages and value of the platform are in the conversations that we have on our platform and the aim to have as many diverse perspectives as possible. We want to include different points of view, raise different voices and make sure that it’s an inclusive space that gives the complete picture of what Open GLAM is. We understand what are the challenges that different communities have, depending on where they are in the world or what characteristics their collections have. It’s about having a holistic approach to seeing how opening up collections is a benefit to society, with all the nuances that are necessary to be in line with specific particularities of different regions or communities. I think that one of the greatest values of this platform is that it enables us to have that kind of wider outlook on what open GLAM means across the world. We commissioned eight open GLAM experts through the platform to understand what open GLAM means in the Global South or for underrepresented or marginalised communities. What are the means and challenges for all of our community? Like I said, that might be very, very different perspectives on what open GLAM means.

KP: Opening up is often a big step for cultural institutions on different levels. It often starts with policy within an institution and understanding at the top management that opening up is necessary, and before the management sees that there has to be a staff consensus. How can the future Open GLAM platform empower cultural heritage professionals to take the step together?

BV: We start with creating momentum by nourishing the movement with the enthusiasm that we have, the ideal of better sharing and what higher purpose this might serve. We do that by hosting community meetings, communicating, supporting the members of our community in their own initiatives. We have a multi-pronged approach which is why our program also has many components. If we want to help individual institutions, we can do two main things. We can provide capacity building training and we can provide consulting advice on the capacity-building side. That’s mainly through our GLAM Certificate.

For many years Creative Commons has offered a training program that’s targeted at practitioners working in libraries, educational institutions, legal and cultural institutions, and it’s through that program that we can communicate and transmit our knowledge about what it means to open up, what the benefits are, and how to do it practically. We focus on how to take those small steps from closed to open and also offer workshops, seminars and webinars to share that information and debunk the myths around open GLAM. Through the training, we give the tools to practitioners and their management, empower them with the language, the ethos of open. It’s all about conveying this positive message of how fundamental opening up is in order to fulfill a GLAM’s mission. In terms of consulting we also can offer tailored advice. We are available for institutions for guidance to understand step by step, depending on where they are and what concrete actions they need to take to open up their collection and that can be:sharing information on copyright, what that means for the licences and tools, how they work, how you apply them, what it means when you apply a Creative, Commons tool to a certain object, what it means for the users, what it means for the institution and taking them along the way along their journey to facilitate and help them go through sometimes, very technical, very legal, very complex questions that they need to solve if they want to make their collections openly accessible.

KP: About the benefits of opening up collections, stressing on increasing reuse. How does an Open Access strategy in an institution fit in a bigger picture of traditional exploitation of cultural heritage and increasing connections to creative industries and researchers to cultural heritage?

BV: I think that one of the objectives of cultural institutions is to connect with the public for their personal enjoyment. People enjoy going to museums, but there are also other users like scholars, researchers who have a different relationship with cultural content and might want to harness that knowledge and information in order to create new knowledge, new interpretations and build on the human experience of interacting with cultural heritage. Another category is artists, the creative Industries. We all know that artistic production doesn’t come out of thin air. Every creative product is born out of something else, of an artist’s experiences of their environment, of what inspires them around them. And a lot of that inspiration comes from the public domain, from this extremely vast pool of cultural expressions that are free for anyone to use in any way that they wish, it can be for the creation of new cultural products, new cultural output. It can be for commercial or non-commercial purposes.The value of the public domain is that it serves as an unlimited reserve of inspiration for new artists, new designers, new creators that can draw from that in order to create something new and therefore participate in this positive cycle of cultural regeneration and creativity.

And I think that online, with new technologies, the possibilities are increasing. We see new ways to generate cultural output, thanks to new technologies. It’s important that GLAMs participate in that movement so they are not preventing progress and are not preventing access to artists using new technologies to create new culture and enrich our lives with new cultural expressions.

KP: What is your best insight into shifts in the use of digital collections, of new reuse and educational programs that have been ignited since opening up the digital collections of institutions?

BV: The Smithsonian Institution had an extensive collaboration with Creative Commons. It took a decade from the idea of making their collection of over two million items available, from the initial idea to actually making it happen. Effie Kapsalis said once, reflecting on the fears that some had had of making the collection openly accessible: ”the sky didn’t fall, right?”. Many institution practitioners were very apprehensive or very hesitant and really didn’t know what would happen. And the sky didn’t fall. On the contrary, the sky opened. Many opportunities evolved for school children to interact with their collections in new ways. They were able to provide all sorts of resources when schools were closed due to the Covid19 pandemic. School children have access to educational content that they can enjoy while not being able to enjoy classroom teaching. To me, that’s one of the greatest examples of how cultural institutions are so integral to our lives that they need to be there online. We and they need to be reachable online because so much of our cultural and social interactions happen online.

It might have taken a decade, but they are there, and it’s a big example.. It takes a long time to start but then when it starts it’s huge.

KP: What are the most exciting and unexpected cases of reuse for you personally, since you’ve been working with open access?

BV: I am always amazed by how researchers within digital humanities can actually put their hands on thousands of reproductions of public domain collections and organise them in databases. And I found it really incredible how you can change the story or any work that has been done on collections with the fact that you can search through databases with different tools and organise your research in a very different way than what we could do before, to have access to those contents.

For instance, the Art Up Your Tab was a browser plug-in that displayed a new work every time you opened a new window. I think the images are taken from the Europeana database. There’s also a collaboration between Paris Musees and the public transport company in Paris. I think this collaboration is pretty cool and catchy.

KP: What is your personal last message to the doubting institution professional to choose the path of open?

CF: The last thing to say is that if you are not online, if you are not visible then you don’t exist. We need to ensure that cultural heritage is going along with society, it’s very important. So I would say go for it. And as I said, I feel like it’s a misuse of all four companies. Well, I think that’s maybe I think

The message to the cultural institution that’s hesitating to open up, is to take baby steps and don’t be overwhelmed by it is the greatest gift that you can give to your users and it’s the greatest realisation of your purpose. Opening up is the way to provide the best access possible for your users, so don’t be overwhelmed, don’t be scared. Take it step by step.

KP: Thank you Brigitte and Camille for sharing your insights into the new future and new value for cultural institutions.