Episode 1:

A conversation with Merete Sanderhoff

Merete Sanderhoff is an art historian working at SMK since 2007. She is curator and senior advisor in the field of digital museum practice, and responsible for the museum’s open access policy. Her work touches upon fostering active re-use of the museum’s digitised collections for research, learning, knowledge sharing, and creativity. Merete is also a member of the advisory boards of inDICEs project and Europeana Foundation.

Kristina Petrasova has a background in Cultural Heritage Studies and production of cultural cross media projects. From 2019 she works at the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision as project lead digital heritage and public media, focussing on education and re-use of digital audiovisual heritage in creative industries. She is part of the inDICEs project in the area of European intellectual property framework.

*Images used in this article are from SMK Open

KP: Let’s talk about the sustainability of open access models. The COVID-19 pandemic’s influence on digital development shows how important it is to build on visions for the future. Digital strategies are quite resourceful, so what are the core benefits for heritage organizations to consider being open, despite the challenges and potential risks?

MS: We live in a time of overwhelming amounts of information and we see the disruptive consequences of misinformation to our democracies. The big sustainable idea of opening up collections of knowledge institutions with trusted resources, is that people can rely on the information. It’s a way of balancing the tendency of misinformation. Keeping trusted resources behind restrictive measures, means a serious risk that cultural heritage collections won’t be part of the public conversation and dialogue. We have to face the condition that the most important reason for sustainability is remaining relevant as institutions in today’s society. There’s an obligation to open up. The point about societal obligation of cultural heritage institutions to share fact-based information openly is inspired by a new book that just came out by Peter Kaufman, ‘The New Enlightenment and the Fight to Free Knowledge’. We should consider an obligation today to share knowledge freely in order to protect democracy and protect the liberty of the open world.

At a more practical level, there’s sustainability in designing and putting into practice flexible open infrastructures for your collection, because there’s so much to gain from having multifaceted communication with the outside world. The perks of open collections are for instance linked open data that are being enriched by Wikidata, the semantic web, the users being able to connect with other open collections. A major reason for sustainability of open collections is that people can help you sustain them.

KP: For a smaller institution dealing with financial and legal resource deficit it could be difficult to begin, how to start?

MS: By now there’s a big accumulated experience within the sector, a lot of knowledge to build on and to learn from, so you’re not starting from scratch. A great way to start is to get in touch with a local Creative Commons chapter for legal advice. If a small institution doesn’t have capacity to get the collection digitized with all the metadata, try reaching out to the local Wikimedia chapter. There’s great value for Wikipedia in having access to your open collection and they host images and information from GLAMs. Wikipedia is an open resource disseminating fact-checked knowledge to everyone in the world, so they need open content to do the work. Through the Wikipedia platform your collection can be displayed, reaching millions of people globally. And it’s community based, helping each other with access to knowledge. The impact in having your collection available on Wikipedia can be huge. For instance, SMK’s images generate more than 37 million page views a year across Wikipedia.

KP: What example of open access would you name that has had a great impact?

MS: One of the great beacons in the OpenGLAM movement has been the Open Data project by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. There are several papers and conference talks about their collective collaboration with Wikipedia and the impact it had. In Denmark too, we have had continuous collaboration between GLAMs of all sizes and the Danish Wikimedia chapter since 2015. Seven cultural heritage institutions share collections and data with Wikipedia. Wikipedia’s staff help us understand how the platform works and how we can get in touch with users who are interested in using our collections. At an early stage of collaboration one of the museums, The Hirschsprung Collection, a small institution, wanted to release part of their collection. At that time no website was available where they could feature an online collection, so they published high resolution works in the public domain on Wikipedia. It’s an example of how to get started even though you have no real digital capacity in your staff.

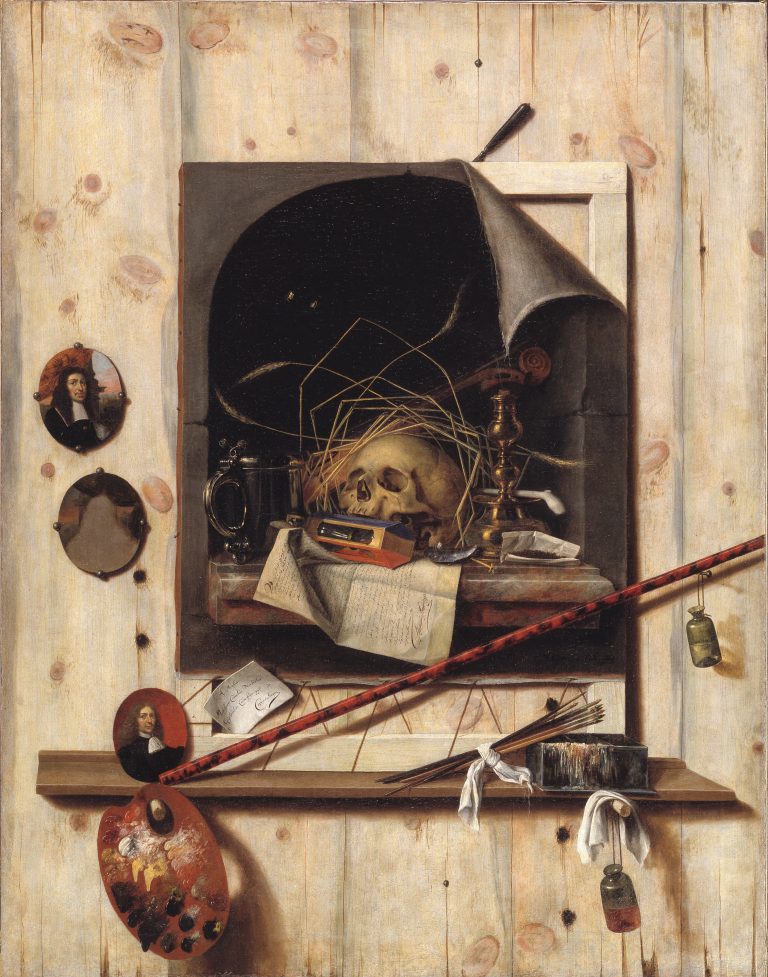

Gijsbrechts , Cornelius Norbertus

KP: So if the technical and the legal sides of open access are challenging, how to inform and train institution staff to acknowledge the benefits of opening up, overcome the challenges and make decision making collective and sustainable?

MS: GLAM professionals everywhere are going through a big change, and awakening. We need to learn about digitization and how to use it in our work step by step, but we’ve come a long way in terms of coordinating that capacity building. One of the hubs for this knowledge is Europeana. It’s free to be a member and you meet other professionals who are struggling with the same challenges. You can join various communities targeted at the topics you’re interested in, for instance Copyright, Education and Tech. It’s empowering to participate in task forces and working groups. Many free tools and webinars are available, and Europeana has developed helpful frameworks about to leverage the challenges we share across the GLAM sector, for instance the Publishing Framework that helps you improve your data quality and make it fit for your target users, and the Impact Assessment Framework, that guides you to define and deliver the impact you want to have on your audiences and society at large. Europeana is a really important place for capacity building in our sector.

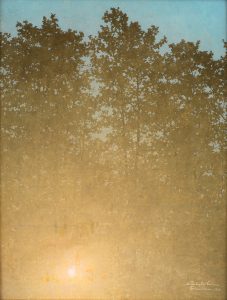

Sunset. Fontainebleau, 1900

KP: Is that how it started at the SMK, with one or two very inspired people who self learned and presented a plan?

MS: We started out being pretty naive. We were excited about the new possibilities that digitization gave us as museums: Suddenly we could connect our own collection with other collections and open up new pathways through art history. But very soon, we bumped into steep barriers of licensing and copyright. Digitally connecting an artwork from SMK with an artwork from another museum turned out to be cumbersome and expensive. That made us realize that it would be a benefit to share images more freely among cultural heritage institutions so that we can boost each other’s collections and open up their manifold possible meanings to the public. Quite simply, we wanted to take advantage of new technologies to organize our work in an easier way. With the Sharing is Caring conference in 2011, we started to share the things we were learning in this OpenGLAM movement that was spreading globally.

KP: You mentioned a big benefit for the daily practice museum staff to have an open collection, and how opening up collections is not only interesting for the people outside the museum.

MS: The internal workflows at SMK were very old-fashioned. To use images of works for the website or for social media you had to send a request to the photography department. I almost forgot how insane that workflow used to be. It’s obvious that the infrastructures around collections, data and resources are evolving. Developing a smarter way to work, a more efficient way to help people to access collection material should be the backbone of any cultural heritage institution today. An important ethical background for this is the fact that cultural heritage institutions are taking care of heritage that belongs to the public, as Peter Kaufman said in his keynote at Sharing is Caring 2021. He made a very important point: Some of the heritage we steward is in copyright, but that’s temporary. There’s a kind of natural law of gravity about copyright on works, because eventually they fall out of copyright into the public domain. I really like to keep in mind that metaphor; there’s a law of physics of cultural heritage. In our sector, there is a tradition to feel entitled to decide what cultural heritage should be used for. As GLAM professionals, we have a very strong bend towards learning, education, research, which is fantastic. But there’s also deep value in experimentation, in having fun and being playful. This was a key point of artist Kati Hyyppä in her keynote at Sharing is Caring 2021. One of the beauties of having a digitized cultural heritage is that you can do all kinds of things with the endless copies without breaking the originals.

KP: That is an inspiring thought, being able to play with cultural heritage.

MS: We should let the public play, yes. One of the key takeaways for the Sharing is Caring 2021 audience was that there’s value in play. It’s good for us humans to play.

KP: The idea of value in ‘play’ is very interesting. How does an open access strategy fit in the bigger picture of traditional exploitation of cultural heritage?

MS: To me, it fits logically because as knowledge institutions, we have always had this position in society of being hubs of education, of learning, of seeking information, of fighting misinformation and of being trustworthy. We live in an age where there’s a lot of distrust in authorities. Cultural heritage institutions are among the public institutions in society that people still trust. So there is clear strategic value in integrating open collections into your future vision. It’s just taking the GLAM tradition into the 21st century with its new technological potentials.

KP: Did you notice any shifts in reuse and educational programs since opening up digital collections? How did the institution change and what are the plans for the future?

MS: We have definitely seen a great shift in reuse. Before we opened up, our images were mostly used in research publications, by other museums, in catalogs and art historical publications. Let’s say, for more traditional purposes. Today we see our digital works used for things that we wouldn’t have imagined back then. Our collection is used amply on Wikipedia for a wealth of different topics. Our open data sets are used for technological innovation, for instance students from IT universities and app developers use our collection to build their own interfaces.

Regnspover klar til at lette, 1911

When the Netflix series called Alias Grace came out in 2018, a colleague made me aware that the scenography was full of artworks from the SMK collection. The beauty of having them in the public domain is that everyone is free to use them without asking permission. But of course, as museum professionals, we are keen to help people find source materials about the artworks. What we did was to add a paragraph to the Wikipedia article about Alias Grace with information, pictures and metadata about the works and links back to SMK. So if you’re interested in Alias Grace, you’re likely to read the Wikipedia article and that will lead you to the source of the original artworks.

I always say that museum people don’t necessarily have the best ideas on how to use their collection. Being trained as art historians, that sharpens but also limits our view. Other people with other backgrounds see other potentials in the collection, and that’s amazing.

KP: The fact that museum collections are being seen worldwide through a Netflix series is inspiring. But do you think this is missed out revenue for a heritage institution, especially if you consider that many institutions struggle with lack of resources?

MS: The whole question of developing new business models in the digital age is a big challenge and I think we are all trying to figure it out. But I am sure Netflix would never have contacted SMK for those images. If they were to buy images for a production, it’s more likely they would have gone through an image library and found ‘the usual suspects’. In this case, they could find and use some new and unknown motifs and thereby make them discoverable to their audience. To say that we could have made revenue here is an impossible scenario, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t think about how to develop business models.

New ways of making money digitally are developing fast now, because of the covid-19 lockdown of broad cultural life. Being cut off from our normal ways of income through physical access and events, we’ve had to rethink both how to remain present and relevant, and how to make money in a virtual setting. Young people especially seem willing to pay for digital experiences of culture, and we have a lot more to learn in that whole new arena. I’m no expert in this field, but it’s important for me to stress that there’s no sense in going back to charging for access to the basic service of digitized images. The internet is full of free images, and if you as an institution don’t offer access to your collection yourself, people will just find free versions of your images elsewhere. We have to be more inventive. But the good news is, people are willing to pay for something that gives them an added value, it’s really rummaging right now.

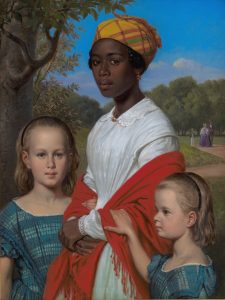

Portrait of Otto Marstrand’s two Daughters and their West-Indian Nanny, Justina Antoine, in the Frederiksberg Gardens near Copenhagen, 1856-1857. Marstrand , Wilhelm

KP: There is not one solution for defining business models for heritage institutions in the digital age, because we are just in the beginning. What new business models do you see developing thanks to the open collections?

MS: We’re experimenting and learning. Our museum shop has a growing assortment of products based on the open collection, and we’re constantly in dialogue with all kinds of designers who are interested in developing a line of products with works from the collection. In terms of new offerings that people are willing to pay for, these are definitely areas that can be developed.

We’ve had a jewelry design contest with Shapeways where people can design 3D models, print them and offer them on a marketplace. This contest challenged the jewelry designers to create new works based on our open collection, the winning designs were sold in our shop and were displayed in the museum.

Also, we organize lots of events that exist at the intersection between social and educational. Not just your classical art historical lecture, but inviting people who are known for their expertise elsewhere for a conversation that opens up new perspectives of understanding the world through the stories and the emotions that artworks give us. Such events have turned out to be a promising new line of business for the museum both in the physical and virtually during the pandemic.

The Painter Agnes Paulsen, the Artist’s Sister, at her Easel, 1886. Paulsen, Julius

KP: In our first call you mentioned the relationship with the private sector. How did that change?

MS: It’s definitely a next frontier for our sector to explore how GLAMs can combine this important open movement with developing new business models. What can we learn from the private sector and their knowledge of how to turn a concept into a business? This doesn’t have to be opposing sides. Zuzanna Stanska gave a keynote at Sharing is Caring 2021 about turning the educational startup DailyArt into a regular business.

The GLAM sector is under a lot of pressure financially. We have to find ways to make our commercial activity wanted and relevant, while considering that heritage institutions are also already financed by taxpayers’ money. We have to balance between the fundamental service we provide and the extra offerings that are so meaningful to people that it makes sense to pay for them.

As a sector, we have created a very strong foundation of openness over the past years. There are more than a thousand GLAMs in the world using open licenses and the number is growing. We are at a stage where openness is no longer a new idea, but something that’s become manifest in society. More and more, users are starting to expect from us that we offer access to the basic collection. Looking at where we are now, there’s maturity and headspace in our sector to start thinking about where to go next.

KP: Thinking about where we go next. Start small…

MS: When we started this journey at SMK, Michael Edson who was then the director of Web and New Media Strategy for the Smithsonian Institution, gave us this very impactful advice: think big, start small, move fast. A great piece of advice, especially when big change might feel overwhelming. The success stories of big institutions might seem too far to reach, but you can do a lot just by starting small while keeping a clear idea of the bigger impact that your institution can have in your local community, in your region, nation, and in the world. We’re all part of a bigger movement in society to ensure that everyone knows it’s their heritage. It’s yours to enjoy, to use, and to build on.

KP: A great final statement, heritage is yours to use and to build on. Thank you very much Merete, for the conversation.

We will go on with this series discussing the future value of open access and we have asked Merete to nominate a colleague via Twitter for the next episode. Stay tuned!